“Can the dissemination of science be a profitable business? Never before has the scientific community felt so much pressure to validate and legitimize what is produced. Can Open Access repositories be the solution?”

These are questions raised by DEI faculty members Carlos Baquero, João Cardoso, Pedro Diniz and Rui Maranhão, which open the recently published guest column in Expresso, transcribed below:

The publication of scientific articles in conferences and reference journals is one of the most important activities for the dissemination and progress of science and knowledge. Recently FCCN, via B-On (online knowledge library), established another protocol in order to create more favorable conditions for the national scientific community to publish scientific articles in Open Access. Publishing in Open Access has the advantage of allowing the reading of articles without subscription costs.

Whereas in the classic publication system the costs were usually covered by institutions subscribing to journals for their researchers’ use and they could usually opt for Open Access at additional cost, in the single Open Access system these costs are transferred to the point of publication and usually covered by a research project assigned to the authors. These protocols aim to reduce these costs, usually with discounts on the article processing fee.

Without going into the polemic on the lucrative business of publishing houses specializing in science, it is easy to observe that there has been a transfer of the moment when publishing houses are financed. In the classical system authors submitted their work, it was evaluated by other scientists, improved and, if accepted, published in the journals, without any transaction involving the author (it was usually the libraries that assumed these costs).

Under Open Access, which generally requires such processing fees, the author has to secure funding after the article is accepted in order for it to be published. Although in theory you are not paying for acceptance of the article, and this depends only on its quality, economic incentives change the landscape somewhat, as there may be more pressure on publishers to maximise the number of articles published.

Despite this risk, publishers have an interest in preserving their prestige and the prestige of the journals they publish. By selecting a small number of articles of the highest quality, they provide an important editorial selection role to their readers, to the fields of science themselves, and improve the potential impact of each article. Several classic journals support both modes of publication, with Open Access being only one option and accepted publications being published at no cost to the author.

Results published in top journals such as Science and Nature have enormous visibility both in the scientific community and sometimes in society at large. However, as these publications are very selective, they require several months of preparation by the authors, prior to the actual submission of the article, and significant improvement and additional work during the demanding peer-review process. In a “fast food” society there does not always seem to be time for these lengthy “slow science” processes.

In the last decade, along with the growth of Open Access, there has also been a growing supply of Open Access journals that promise very short peer-review times, making them very desirable for junior researchers wishing to enhance their academic profiles. To take the proverb “Quick and well, there’s no who” we can observe that there are limits to the efficiency gains that can be made when reviewers are usually other scientists, unpaid by the publisher, with little time available, particularly when they are well-known scientists.

In these publishers, achieving efficiency invariably leads to editorial boards with several hundred members, usually little known, in contrast to the usual ten or so names recognized by the community and with a clear role in the selection of articles in reference journals.

Other mechanisms to ensure a profitable business model seem to rely on the creation of numerous special issues by invitation and on the massive invitation to various scientists to prepare these issues; often in areas that they do not dominate or in which they are not recognized. Scientists have even been enticed by offers and reductions in Open Access costs, a strategy that ensures the involvement of many and the reach required for a profitable business model. All of these factors greatly diminish the perceived quality of the articles selected.

This decline in publication quality has recently been discussed in other European countries, with somewhat disparate approaches. The potential impacts of these practices on the quality of science have been discussed in a paper from KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden; in our neighbour Spain the increasing migration to rapid publication media has been discussed. In some countries, such as Switzerland and the United Kingdom, these channels for the dissemination of scientific results are simply ignored or even unknown. There is even a rejection posture in reference institutions, in which researchers with extensive or significant part of their publications in these channels are not taken seriously.

Perhaps this phenomenon of rapid publication of unripe results is not unrelated to the observation that there is less and less impact of research on the transformation of society, as documented in a recent article in Nature.

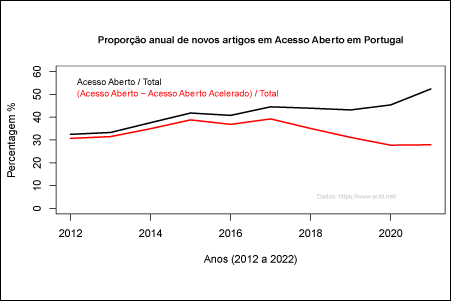

The rapid and massified publication via these publishers has been too tempting for early career scientists, for a scientific community subject to immense competitive pressure and where regular publication is essential for career development. In Portugal, we can see that the growth in the proportion of Open Access publications over the last decade (black line) would not have occurred if the effect of publications in two large accelerated publishers were discounted (red line shows what the proportion would be like without these publications that we call Accelerated Open Access). The effect would be even larger if other smaller journals associated with what might even be called predatory practices were discounted.

While Open Access can be positive for better dissemination of research results, this should not be at the expense of lowering the quality of publications. Just as a little occasional fast food has little impact on our health, so a certain amount of fast science seems reasonable. Not all research always produces the results the authors would like; there is competition and sometimes other teams publish first.

However, it is no longer healthy, as with a primarily fast food diet, for the bulk of publications from a given researcher, team or institution to begin to be of this type as a rule. Many articles that could reach top journals end up not realizing their full potential by being directed to these rapid publication channels.

Indeed, the existence of pre-publication repositories such as arXiv and medRxiv enables rapid and open dissemination and it is suggested that these channels (rather than Accelerated Open Access) be used for that very purpose, allowing authors to refine their articles and even raise their quality (in terms of data extensibility and/or more robust reasoning for conclusions) by publishing them in other channels with longer peer-review stages.

Worse than the development of a quick, metro curriculum, the current approach is itself counterproductive for authors, as it does not allow them to realise their full potential and may, in the long term, impact negatively on their careers. A cornerstone of the system is individual research freedom; authors are sovereign in their choice of publication targets. However, it is important to be aware of the existence of journals with more massive and potentially predatory strategies. Twenty years ago, it was relatively simple to distinguish good journals from journals with practices that could be classified as predatory, the latter being very artisanal and unprofessional. Today the line is much more blurred, partly as a result of extremely profitable and very successful business models.

It seems therefore very important to us that the national scientific community avoids the dominance of “fast science”, namely by avoiding that the new generations of scientists fall into the temptation of the easy enticement of these business models that gravitate towards science.

This guest column was published in Expresso on 21 February 2023 (09:33).